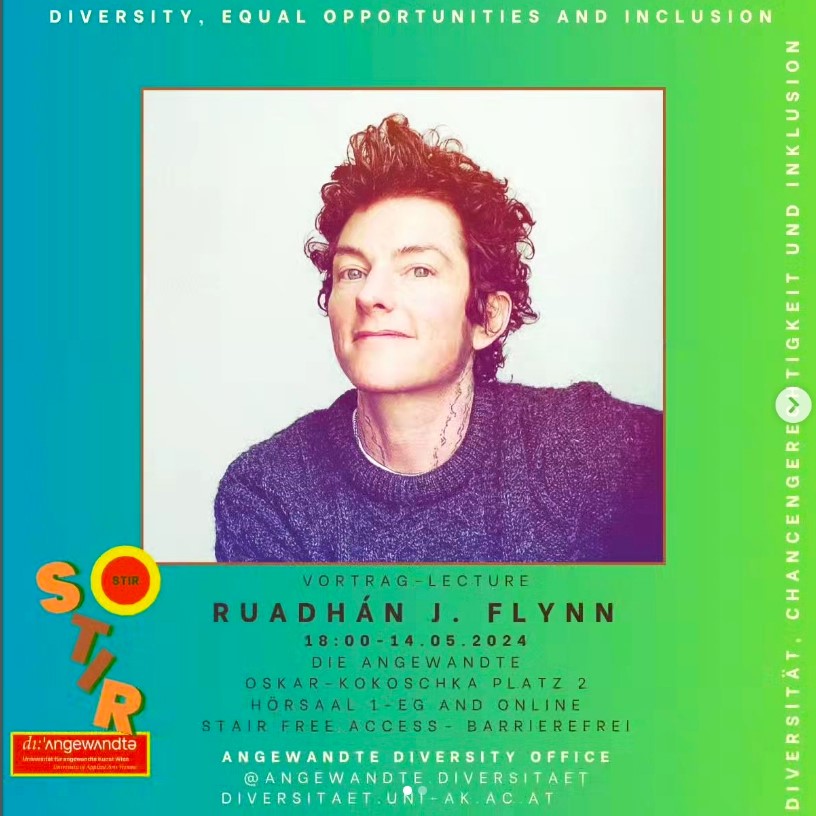

This page includes the recording and resources from a public lecture on May 14th 2024, as part of the STIR Public Lecture series, hosted by the office of Diversity, Equal Opportunities and Inclusion at the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

Accessibility: The audio and captions are in English. There is no Powerpoint or slides. The full transcript is at the bottom of this blog post, after the references.

Citation: Flynn, Ruadhán James. “Futures, Imagined: Disability, Eugenics and Science Fiction”. YouTube, uploaded by Ruadhán J. Flynn, 17 May 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AEHOsHNiWbA.

FUTURES, IMAGINED: DISABILITY, EUGENICS & SCIENCE FICTION

Abstract:

Egalitarian visions of the future typically portray harmoniously diverse societies, where divisions along racist, economic, and religious lines have been overcome. Such futures are(typically) also curiously free of disabled people. It remains a widespread assumption that a better future will be one in which disability(understood as an error or failure in individual bodies) has been eliminated.

Yet this assumption aligns with eugenics; itself an exercise in science fictionwhich aimed to manifest a vision of a purer, stronger, white supremacist future by eliminating supposed-inferior and defective strands of the human species. Doeseugenics still limit our individual and collective imagination? And if “all [social]organizing is science fiction” (Imarisha, 2015), how are our movements for social justicein the here and now affected by thedistant futures we imagine?

References and Resources:

Garland-Thompson, Rosemarie. “Building A World with Disability in It”. Culture – Theory – Disability, Vol.10. 2017. DOI: 10.14361/9783839425336-006

Imarisha, Walidah. Essays & Projects: https://www.walidah.com/blog?category=Essays

Lazard, Carolyn. Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and A Practice. https://promiseandpractice.art/

Moore, Leroy F. Interview: https://shadesofnoir.org.uk/content/in-conversation-with-leroy-f-moore-jr/ / Krip-Hop Nation: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCdwxjCpfkg9EZQEYhlU5HVA

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. “Disability Justice: An Audit Tool”. 2020. https://www.northwesthealth.org/djaudittool

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. The Future Is Disabled: Prophesies, Love Notes, and Mourning Songs. 2022.

Sins Invalid. “What is Disability Justice?” https://www.sinsinvalid.org/news-1/2020/6/16/what-is-disability-justice

Shew, Ashley. Technoableism: Rethinking Who Needs Improvement. 2024.

Shew, Ashley. “From a Figment of Your Imagination: Disabled Marginal Cases and Underthought Experiments”. Human Affairs, Vol. 30, 2020. DOI: 10.1515/humaff-2020-0054

Kirby, David A. “The Devil in Our DNA: A Brief History of Eugenics in Science Fiction Films”. Literature and Medicine, Vol. 26 (2007).

Weise, Jillian. Essays. https://jillianweise.com/cyweiseessays

TRANSCRIPT:

Right, [waves] I can’t see the camera so hopefully you can see me. Okay thank you, thanks for coming, I know there’s a lot else on this evening so I appreciate people being here. Thanks Iketina for the invitation to speak, and thanks Daniel for all the help. The problems with accessibility for this event are as good an illustration as I needed for the talk I’m about to give, so I appreciate the effort that’s gone into it regardless. It certainly wasn’t a case of people not making… not trying. I want to thank also the vice-rector of the university for taking time to be here, and before I start the lecture proper, I want to start by expressing my full support to the students of Die Angewandte Free Palestine. They have provided the university here with a list of very well-considered, principled and productive demands in response to the ongoing situation in Gaza, and I respectfully suggest that the university management sincerely and openheartedly engage with those demands.

We’re going to talk about building better worlds, and about what we mean by better. I’m going to tell you that actions matter. I’m going to tell you that the big ones matter and the smaller ones. I’m going to tell you that how we imagine matters, both imagining in the world we’re in and imagining the possible distant future worlds that none of us will live to see. And I’m going to argue that there is a decisive, generative connection between how we envisage those distant futures and the actions we take day to day. I’m going to talk about disability to do this. Disability as one system among others through which we ascribe meaning to difference. You will no doubt see similarities between this and other systems. To really talk about disability I have to talk about eugenics, a bit about its roots and history but mostly about how eugenic logic – which some people, I think, imagine is in the past – still permeates how we imagine disabled lives now and in the far future, if we imagine them there at all. And I’ll illustrate that by looking at disability access and accessibility, how we go about providing it and on what basis. I’ll be inviting you to check in with your own imagination, to take a few seconds here and there to see what your imagination throws up when you consider these things. And finally I’m going to talk a bit about science fiction. Science fiction as a cultural product, and what that tells us about how we think about disability now and in the future, and science fiction is a cultural practice, following Walidah Imarisha, as a way of radically imagining the futures we want and allowing those visions to guide our actions in the everyday. We’ll hopefully end up with a counter-eugenic argument for imagining and building better worlds through disability: not grudgingly planning for disability as a charitable accommodation, but relying on disabled knowledge and imagination as the radical, adaptable, creative wellspring that can save our lives in apocalypse. I’ve got about 45 minutes so we might as well go for total revolution.

So let’s start with disability. There’s no slides by the way, so this is just going to stay as the title screen for for the rest of it. I want you to start this by imagining. You don’t have to share what you imagine, this isn’t performative in any way, it’s just between you and yourself. Imagine a disabled person.

And pause the image, and we’ll come back to that.

So, disability is a mobile, contingent social-political category. That means that it’s never clear who it does and does not include. And I’m not aiming to provide clarity on that. I’m not going to tell you who is or is not disabled. Instead we’re going to look at how disability operates and what that can tell us about how we got to where we are, and where we’re going. There’s a lot of different ways to talk about disability but I’ll start with a common distinction. I appreciate that most people don’t have any contact with disability studies so we’ll go with the basics for for a line or two. The historically older idea is that someone is disabled because something is wrong with their body, right; they can’t walk, they can’t see, or they can’t think and understand like most people can. This is usually loosely called the medical model of disability. It means identifying features in individual bodies which require diagnosis, and which are understood as faults, as defects, as things those individuals lack. And this was countered by what’s generally called the social model of disability. On this understanding there’s a distinction between an impairment, which is the aspect of your body or mind that marks you out for disability, and disability itself, where disability is now the system of social discrimination and disadvantage that affects people with impairments. Hence calling it the social model of disability. It points out how almost every aspect of societies, from architecture to arts and culture, from education to workplaces, every aspect is designed on the presumed absence of people with atypical bodies and minds. Society therefore actively disables people by discriminating against them… I’m just going to click that one, sorry the computer is trying to uh restart again… So, the medical model and the social model have been around for decades and they’ve been thoroughly thrashed out and critiqued and reconfigured. I’m not aiming to give you like a full history of disability studies or disability activism. Instead here’s a few overall things to consider. I think, these days, most people understand that there is something going on at the social level when it comes to disability. That it’s somehow not fair that people can’t access buildings or events or social spaces because of some condition of their body or mind, how they move, how they speak, how they think. There’s a general awareness that disability is in some sense an equality issue, or even very tentatively a social justice issue. But I find that if we press a little harder on that awareness it quite quickly turns into the same old medical model. Disabilities are still typically thought of as individual features of individual people. They are still pervasively thought of as lack, as loss. The disabled person is a normal human minus some specific capacity. And I say this because what whatever nods are given towards disability as a social equality issue, disability access – which is the main way we confront disability – predominantly still works on a charity model. Underneath the nods towards fairness and equality, disabled people are still thought of as people who lack the ability to take part in normal society because of something they lack as individuals. So accommodating that lack is pervasively understood as an optional act of benevolence or charity. Accessibility is still understood as the accommodation of special needs, as if there was anything special about being able to go to school or use a public bathroom or use public transport. Accessibility is frequently peacemeal and partial, so maybe there’s wheelchair ramps, maybe there’s sign language every now and then. So the dominant approach to accessibility still imagines that access means providing specific, discontinuous, temporary services to specific individuals on the basis of something they are tragically unable to do, and it proceeds as if providing these isolated, limited, discontinuous services were an entirely optional act of charity and kindness.

The primary approach of disability rights movements over the last 50-odd years has been, clearly, to frame this as a matter of rights, of legislation and regulation, of laws and requirements. This is a punitive approach aimed at forcing institutions and organizations to provide access, mostly understood as physical access to built environments, or risk fines and legal repercussions if they don’t. So there’s no doubt that the disability rights movement has achieved profound societal change in certain places and primarily of benefit to certain people. However, I think there are pretty significant limitations to this approach, especially moving into the future. These limitations become all the more obvious when you try to expand this approach beyond the places where it took hold, namely North America and some parts of Northern Europe, and beyond the kinds of people who are the primary beneficiaries of a rights-based approach, namely English-speaking middle and upper class white people with mobility and sensory impairments. If this sounds a bit like white feminism you’re on the right track. A punitive, legislative approach benefits people who already have a certain kind of social standing. That’s something I’m going to loop back to towards the end of the talk. But more importantly for now, a strategy of forcing societies to provide services that they still view as charity for tragic cases has a limited shelf life. When disability is still pervasively thought of as a deficiency, as lack, as tragedy, when disabled people are still pervasively thought of as a social burden, as human-minus, as suboptimal and subnormal in all kinds of life, as objects of pity or worse – well, you can spend your life taking accessibility cases to court and there’s still very little you will change for the vast majority of disabled people. Disabled people are still thought of as disposable societal burdens, something we saw vividly during covid-19. Disability care and accessibility are still seen as optional charitable extras, regardless of the legislation, if we feel we have enough money left over after everything else. So with those assumptions still undergirding our decisions and our actions around disability, no amount of legal conpunction is going to save us when societies destabilize, economies contract and the struggle for resources intensifies. We don’t need a climate emergency to teach us this lesson. In both the past and the present, we find plenty of evidence.

But there are broader issues with this rights based approach, issues that should make us question who we assume we’re including when we say disabled people. So a few minutes ago I asked you to imagine a disabled person. Bring that back to

mind.

Now, most people, especially in Euro-American context, will imagine a white person in a wheelchair, or a white person with a cane. Imagined disabled people are typically white and they usually have a visible disability – but not too visible, we don’t want anything disturbing or monstrous. I’ll talk about that more when we get to science fiction. But first we need to talk about eugenics. [laughs]

So, one way of framing eugenics is that it is science fiction. That it is a project of using various material and social technologies to intervene in the present, to determine the human species in the future, guided by an ideology of what kinds of humans they should be.

Rosemarie Garland-Thompson, who is one of the key initiators of the field we now call critical disability studies, she says that eugenics is about “controlling the future by shaping how human beings are and who we have among us”. Now that idea – the idea that we should get rid of suboptimal or unfavourable kinds of people now so that they’re not still around in the future – that’s a very old idea. It still seems to be, I would argue, quite an intuitive idea for a lot of people. But eugenics, specifically takes shape in the late 1800’s, at a confluence of imperialism, violent extractive colonialism, and evolutionary theory. Its formalization is attributed to Francis Galton, who was a cousin of Charles Darwin, and Galton proposed eugenics as “the science of improving human stock”. He combined what were then new discoveries from animal breeding, with an interpretation of his cousin’s theory of evolution, and filtered those through an ideological lens that already assumed certain kinds of people were superior for certain kinds of reasons.

Now, eugenics can be analysed and discussed as an ideology, as a social movement, and/or as a set of… specific kinds of pseudo-scientific practices aimed at controlling the make-up of human populations. It’s all of those things. It was presented as a plan for intergenerational human improvement – and by intergenerational they meant controlling who could and could not reproduce, and who could and could not live in the improved world they envisaged.

In practice this meant a wide range of medical and social technologies: forced and involuntary sterilization, miscegnation laws, segregation and institutionalization. Broader practices fit comfortably within this ideology and method: such as the destruction of indigenous populations through the mass theft and displacement of children – an action explicitly aimed at making sure those kinds of people didn’t exist in the future.

So, eugenics was both an ideological pillar in the foundations of white supremacy and the practices through which white supremacy could be weaponised. Crucially, it provided pseudo-scientific justification for white supremacy, and within it, ableism and social control. Because what we have to understand about eugenics ideology is that it assumed that a very wide range of social problems, and social differences, had biological causes. Early eugenicists saw poverty, illiteracy and violence [laughs] not as consequences of unequal social power, but as forms of moral degenerecy that were passed on from one generation to the next through bloodline. Poverty and illiteracy. And racialized ethnic groups, indigenous, colonized and enslaved populations were classified as cognitively inferior – not individually, and not for any social or cultural reason. Eugenicists shazaamed evolutionary theory to claim that some humans were more evolved and therefore naturally cognitively superior to others. So, the educated white controlling class were – on this interpretation of Darwin’s term – the “fittest”. Their wealth, and their power and their dominant social status were the result of innate superiority. Subordinated and conquered groups were subordinated and conquered because they were innately, biologically weaker, less intelligent and less valuable. Eugenicists claimed – some proponents continue to claim – that social problems have biological causes, and that those biological causes can be identified, can be modified, or eradicated.

So the pseudo-scientific power-move of eugenic logic is to present entirely contingent differences in social power as being the result of innate biological differences. People are colonized, enslaved, oppressed and abused not because some other people seized and abused power, but because that is the natural evolutionary order. Eugenics then aimed to intervene in this natural order to promote the propagation of the powerful, and reduce or eliminate the propagation of people it deemed inferior, deficient, and unfit members of the species.

Now, disabled people – people with the kinds of conditions we still typically consider disabilities today, like deafness, congenital limb differences, or Downs syndrome, for example – were the primary targets of eugenics from the start. But, many, many people who did not have any kind of distinguishing conditions were also classified as cognitively impaired and treated on the same basis – often institutionalized, forcibly sterilized, denied healthcare. These targets were – to different extents in different jurisdictions – primarily poor, Black, or members of indigenous and colonized groups. Even when they had no significant physical or cognitive atypicality, they were classified as and treated as disabled by the same or similar metrics as those with identifiable physical or cognitive differences.

So, as I said at the start: disability is a mobile, contingent social-political category. It’s never clear who it does and does not include. We’re looking at how this category operates. What we see from the history of eugenics is that, in ideas of superiority and inferiority, fitness and subnormalcy, we find that racialization, class and disability are very hard to pick apart. This is not just a recent history – it is an ongoing history. Every year we find out about involuntary sterilization programs affecting incarcerated Black women, poor and indigenous people, disabled people; compulsory sterilization laws for trans and intersex people. State-sponsored programs of explicit, interventionary population control are far fewer, but there are new alternatives which seem to track similar ideological lines, such as restrictions on IVF for single mothers, and poor people, and queer and trans people, and obvious differences in actual ability to access those kinds of services for Black and indigenous families.

In terms of congenital conditions though, the picture is still pretty explicit. With the advent of pre-natal testing, parents are now pervasively encouraged to terminate pregnancies where the child is expected to develop for example, Downs syndrome or limb atypicalities. And disabled would-be parents are heavily discouraged, in some cases legally prohibited, from reproducing. We don’t talk much about subnormacly and inferiority anymore, but we talk about an amorphous thing called “quality of life”. Disabled lives should be prevented because their life quality is so low it’s kinder to erradicate them: so the assumption runs, despite study after study demonstrating that disabled people report similar or higher scores on quality of life assessments than their non-disabled peers. There is no charade around the new technologies like prenatal testing and selective abortion, or the do not recussitate orders or the withdrawal of healthcare. These practices have been and continue to be defended as “liberal” eugenics – a modification that, believe it or not, was supposed to make eugenics sound better – where the key difference is that parents and carers can make these decisions on the open market without any eugenics program being enforced by the state. Which is a hogwash claim that I’m not going to waste my time on.

This is just to illustrate that eugenics is alive and well and doubling down on the core eugenic intuition:

that a better world is a world with no disabled people in it.

So, rather than arguing with promoters of eugenics, a more important question for me is the extent to which that eugenic intuition is held by most people, arguably even those who see the wrongness and violence of eugenics history. I think a lot of people retain the idea that a disabled life is a tragedy. People fear disability. People will openly say they’d rather die than lose a limb or lose their sight. And I think it’s a very widespread intuition that a better world, if we imagine a fantasy of a better future, it is one in which everyone can walk, talk, see, hear, breathe, think, eat, laugh and poop without any special equipment, without any special care, and without any special needs. So, this is the second point where I want you to take a second to check in with yourself. Don’t berate yourself or correct yourself. Is that what your intuition is, or what it has implicitly been?

So, it’s a bit tricky, it’s probably even a bit arrogant, to be making claims about collective imagination and widespread intuitions. So here’s where I’m coming from on this. One of the ways I see the eugenic intuition showing up is in how we do access and accessibility. We do access and accessibility in such a sloppy, uncommitted, ableist way that it’s almost like we’re not planning for disability long term. We’re not planning for people with multiple, overlapping disabilities, or people with mutliple barriers to access (like poverty and language). We’re not planning for there to be more disabled people. On the contrary, we seem to do access and accessibility as though we expect disabled people to somehow disappear.

But another way I see the eugenic intuition showing up is in how dominant cultural modes imagine the future for us. How our interest and attention direct what futures are represented and how. This is the first of two ways I’m going to talk about science fiction: science fiction as a cultural product, so science fiction films and literature, essentially.

Later I’m going to talk about science fiction as a cultural practice, following the work of Walidah Imarisha among others. And if you’re losing hope already, just stick with me. This is how we’re going to get out of the mess we’re all in .

Now, I am not a cultural critic, I haven’t done film or literature studies. I’m not trying to give an in-depth analysis of disability in any specific text or film. I just want to point at some of the broad themes I see in science fiction, that I think relate to how we, different versions of ‘we’, think about disability. Disability now, and disability in the future. The eugenic intuition shows up in different ways, and I’m just going to sketch out a few.

So, science fiction, or if you like, speculative future fiction, I won’t argue anyone on the distinction, is a good genre for getting at things like political intuitions and collective imagination for a couple of reasons. It’s usually the case that science fiction is concerned with the political hot topics of the time and place in which it is made, but by transferring those topics to far distant times and places, it can reveal basic assumptions underneath those topics. So, it can be used to test out ideas for different kinds of social organisation, different kinds of social and political power, although often it instead shows us exaggerated versions of the systems we already have.

In terms of disabled futures, Rosemarie Garland-Thompson has said, “Utopias are without disability and dystopias are filled with it.”. I think this is true up to a point. Certainly in major pieces like the older Star Trek series, more niche classics like Marge Piercy’s “Woman at the Edge of Time”, it is implied or demonstrated that advanced, utopian-ish, more egalitarian futures will, by and large, not have disabled people in them.

There are interesting exceptions though in both of those cases. So in Piercy’s utopian future, it retains some kind psychological disability, but that is still framed as a feature of individuals, and those individuals are required to remove themselves from the community.

And I could spend the whole night talking about Star Trek [laughs] but I’ll just point out that .. Geordy LaForge as an indicative example, anyone who remembers Geordy LaForge from Next Generation. So, this was a character who has atypical sight and he therefore wears this special visor so that he can function alongside everyone else on the crew.

This is a good example because a pretty common model for what we might think of as positive representations of disability in utopian-leaning science fiction. The impairment is discrete, it’s localized, it belongs to the individual, and the utopian assumption is that it can be easily and stylishly fixed through a shiny, discrete and apparently freely available technological device. This kind of technological solutionism is kind of the sneaky, charitiable arm of the eugenic future. Yes, sure there will be some people who have things wrong with their bodies, but we can give them a slick piece of tech to normalize them again. This future fantasy encompasses three of the main disabled critiques of disability tech in the present. One is that assistive tech is designed by non-disabled people with the goal of normalizing what they see as deficient bodies. The second is that tech designers only ever seem to care about bionic arms and exoskeletons, not better tech for respiration, or dialysis, or pacemakers. And third, this techno-solutionist, utopian future trope still vividly imagines disability to be a fault in individual bodies. It is the individual body that has to be fixed, not the material or the social environment. So even in when we do see disabled people in a utopian future, they seem to be only allowed to exist there within pretty tight, conspicuously ableist parameters.

Now, the more dystopian-leaning narratives offer up far more disability representation, but typically as a narrative cue for badness, for despair, for social failure. I want to briefly note two broad kinds of dystopian sci fi, and directions they kind of point us to. In one kind, particularly popular in the nineties and 2000’s, we’re dealing with a kind of AI-gone-wild dystopia. So, in these clean, hyperconnected techno futures, the dystopian concern is with machine-human hybrids, with cyborgs, with human-like technology, partially technologised humans. There is a lot to be said about these films in terms of coded disability tropes, I’m just going to point out two. One is the representation of prosthetic or detachable limbs and body parts and in the coding of this as inhuman, creepy or monstrous. To follow up, I recommend the work of The Cyborg Jillian Weise, the link is in the talk notes.

The second trope I see here is a frequent coding of the machine-human entity along conspicuously autistic lines. So, as with Vulcans in early Star Trek series, contemporary cyborgs are creepy, unlikeable and inhuman because of their perceived lack of emotional expression or empathy and their monotone, formal delivery, which you might recognise from the last 20 minutes.

So, as a less explicit version of the eugenic future, the clean tech futures of creepy AI still seem to lean on coded dehumanizing tropes about disability, and quite worryingly it’s part of a narrative which implies some sort of threat to the integrity of the human species.

These tech futures are otherwise almost free, almost entirely free of disabled people. So, contra Garland-Thompson, these dystopias are not full of disabled people. They’re full of non-disabled white people. And I’m not saying this as a flippant observation. This was the case for decades of science fiction. Almost entirely white representations of future humans on earth, not to mention planet after planet after planet of white aliens. In a few minutes I’ll have more to say about the ability and the inclination to radically imagine futures out of the trash of the present. But first one last point on science fiction as a cultural product, which is going to loop us back to those theories or framings of disability.

So, I said there were, at least, two kinds of dystopian science fiction. One is the tech-bro fantasy AI future I just discussed. And the second is the disaster dystopias. These prominently feature large scale social breakdown, often global viruses or pandemics, or some other kind of global catastrophe, colliding comets, climate collapse, that kind of thing. And with this strand, the picture on disability and eugenic intuitions gets a little bit less clear. These futures often prominently feature disability and illness, and these disabilities and illnesses are a collective problem caused by the dystopian conditions. So, we might see an acknowledgement here that social arrangements, access to healthcare, and environmental factors are decisive in the quality of life of disabled people, that disability is as much if not more dependent on social, structural and environmental factors as on your individual bodily make-up. Unfortunately [laughs], in many such dystopias, the dystopia itself is the only cause of disability and illness. There is still no sign of the run-of-the-mill wheelchair users, Deaf people, amputees, or people with cerebral palsy that presumably lived in this world before the disaster. Now perhaps, if disabled people were even considered to begin with, it was assumed they would’ve died off in the initial stages of the catastrophe. This was certainly the resounding assumption in the last pandemic. But contemporary dystopian science fiction is also just a complicated landscape.

So, in Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s most recent book, “The Future Is Disabled”, they argue that, quote, “BIPOC science fiction writers have a more abundant track record of writing realities full of disability, whether they are utopic or dystopic or complicated” and that includes, they say “both those who claim the D-word and those who don’t… [those] who consistently write worlds that go beyond disability as tragedy or non-existent, where disabled.. characters live with and transform apocalypse out of their disabled genius and guts”. Fans of Octavia Butler or Okorafor will recognise that tendency pretty clearly. It can be seen as well recently at the blockbuster level, so with Olatunde Osunsanmi’s influence at the helm of Star Trek, for example. But, as Piepzna-Samarasinha points out, this doesn’t seem to be a coincidence, that the futures imagined by both disabled and non-diabled BIPOC creators would show up the entanglement of race, class and disability that was constructed in the belly of eugenics. Communities who the eugenic intuition has collectively imagined out of existence, recognise the historical construction of that entanglement, and they reflect into the future the myriad ways that it manifests today. The question for dominant theories of disability and dominant approaches to access which I outlined at the start is: why don’t they seem to recognise that entanglement?

So, before I talk about science fiction as a cultural practice, which will be the last section, let’s just think again about who we imagine when we imagine disabled people. I asked you to imagine a disabled person at the start, but I also said what I’m doing here is not trying to tell you who is or is not disabled. We’re looking at how disability operates in the world and that includes people who were categorized and treated as disabled in the past when they had no particular condition or aytpicality, and it includes people now who might never consider themselves of refer to themselves as disabled. Because a lot of people affected by disability are not in the same position to use the D-word, not in a position to claim disability and claim the concurrent legal protection: not like the dominant voices in disability studies and disability rights can do. If you’re Black, brown, indigenous or otherwise subordinated within white supremacist societies, claiming disability is a risky business. It can lead to redoubled marginalization, it can be feared as a something which naturalizes that marginalization. Yet because our societies are still structured on that supremacist history, BIPOC, migrants, as well as poor whites, are most likely to do the kinds of work that result in chronic illnesses and disabilities: heavy agricultural and industrial labour, domestic labour, work with high exposure to chemicals, high risk of physical injury and long term physical and psychological stress. Many communities have completely justifiable distrust in medical institutions and social care systems. They’ve been targeted for medical testing and experimentation, denied access to healthcare, and are far more likely to be incarcerated and have their kids taken away. Police and prison systems massively disproportionately target BIPOC, and prisons are full of disabled people. Forced migration, displacement, environmental collapse, and militarized violence are all statistically massive causes of disability, and consider who those factors primarily effect. In Gaza alone in just seven months, a conservative estimate is that 140-thousand people have had one or more limbs amputated. Racialization, histories of colonization, and poverty are the prime causes of disability, and if you recall, these are exactly the social groups targeted by eugenics, exactly the same socially-contingent features which eugenicists thought were innate.

So, the way disability shows up in the present, understandably reflects the entangled constructions of race, class and disability in the past. So why do our dominant theories about disability, and our common approaches to access, not reflect that entanglement? If our collective understanding of disability, even an equality-oriented understanding, is rooted in the standpoint of only a particular subset of disabled people, that seems like a very thin understanding. And if our approach to disability and to access is through laws, rights, and legislation, that seems like a very thin method, which conspicuously mostly benefits the same kinds of people.

If universities only provide study and exam accommodations to students with official diagnoses of specific conditions, what does that mean for students from communities who resist pathologisation? Who cannot afford assessments? Who fear being further marginalized if they are seen as deficient? Who do not have health insurance?

If workers can only demand considerations around existing conditions, or pursue compensation for work-related injuries through legal procedures, what does that mean for people persecuted by legal systems? What does it mean for undocumented workers? For people who can’t afford a lawyer? For people who can’t afford to lose their job? We didn’t need the violence of the last seven months to learn that supposedly universal human rights are primarily of benefit to people with the means and security to claim them. That’s not news. The Universal Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons doesn’t mean much under occupation, or if you’re undocumented, or if you have any number of reasons not to identify yourself as disabled.

So the dominant theories of disability and dominant approaches to access can’t tell us much about the lives of the majority of disabled people in the world, and they can’t guide us about how to act on disability, fully conceived. They can’t seem to get us to a future where the needs, basic and special, of the majority of disabled people can be considered. Now, to my mind, the only understanding of disability that can do that is Disability Justice. This is the first framing or the first model of disability that is awake to the legacy of eugenics. From the Sins Invalid introduction to Disability Justice, I quote: “a single-issue civil rights framework is not enough to explain the full extent of ableism and how it operates in society.” Disability Justice is an explicitly anti-capitalist, Black-led movement, founded and developed by disabled queer and trans people of colour. Carolyn Lazard says that in Disability Justice, disability is “an economic, cultural, and/or social exclusion based on a physical, psychological, sensory, or cognitive difference” and that, crucially, disability is “unevenly distributed, primarily affecting black and indigenous communities, queer and trans communities, and low-income communities”. So that’s the big development of Disability Justice from the social model. Disability Justice therefore centers the leadership of those communities, and this is very important for me specifically to emphasise. Leroy Moore, who is one of the founders.. – who is the founder of Krip-Hop Nation and one of the originators of Disability Justice, has been especially critical of the white appropriation of Disability Justice, of white disability scholars and activists using the term Disability Justice to make their work more interesting, without engaging with the central anti-white-supremacy, radical social justice core of it; of white Disability Justice scholars and activists benefiting from Disablity Justice while disabled BIPOC continue to be marginalized and excluded within academia and disability activism. So, the Sins Invalid introduction to Disability Justice says, “what has been consistent across disability justice – and must remain so – is the leadership of disabled people of color and of queer and gender non-conforming disabled people”.

So, accessibility plans that operate from white-led models of rights or charity cannot do Disability Justice work. And all-white or majority white groups or organisations who want to take a Disability Justice approach to disability and access, first have to form community with and centre the leadership of disabled BIPOC. Even all-white organisations who put great effort into intergrated, flexible approaches to disability still have a major accessibility problem. In fact, I would say all-white organisations are a major accessibility problem. If we model our approach to accessibility on what Christopher Bell called ‘white disability studies’, we are not considering the access needs of the majority of disabled people. We are still latently working with a supremacist ideology that doesn’t expect certain kinds of people to be here, not in the present world, and not planning for them in any kind of collective future. The white-led, rights-based approach is not equipped to deal with the coming emergencies. Disabled people outside of that framework knew this already, they have always known this. The fact is, when the shit goes down, no one gives a fuck about your rights.

As well as explaining current disabled reality, and understanding its history, Disability Justice is also a project of radically reimagining the future, as a way of answering the questions, why would we want to imagine a future with disability in it?

Why should we imagine a future with disability in it? So, this is the final part of the talk. Let’s consider science fiction as a cultural practice.

So, this is based on the work of Walidah Imarisha – there’s quite a few resources in the talk notes already, I’ll add more later. Imarisha has been talking about the usefulness of visionary fiction and science fiction for years. She writes that “all organizing is science fiction”. We organize and take actions in the here and now, aiming toward an imagined, different, better future. And in answering why we would and should imagine those futures through and with disability we have to reconfigure how we understand disability and access in the present. So, the proposal is not, as I said at the start, that we charitably imagine ways to accommodate disability. The proposal is that disabled knowledge, adapatability and creativity are needed for all of us to survive in that future.

Rosemarie Garland-Thompson again talks about this by considering what we would lose, besides disabled people, if disability was erradicated. And she argues that disability is “a resource rather than restriction… [that it is] generative rather than limiting”.

Piepzna-Samarasinha writes that “…disabled wisdom is the key to our survival and expansion. Crip genius is what will keep us alive and bring us home to the just and survivable future we all need.”

Ashley Shew talks of disability engendering “creativity and adaptability like no other”.

Disabled people who are multiply marginalized have had no choice but to form networks and communities, to hack, to build, to create, to share, to thrive with significant needs in a hostile environment with the minimum of resources. More than anyone else, disabled people, and especially mutliply marginalized disabled people, know how to live and build hope in chaotic, dangerous, non-ideal conditions.

Piepzna-Samarasinha again writes that in worlds further destabilised by climate breakdown and conflict, we will need, they say, “…all the disabled survival strategies, communities, and tech we create by and for ourselves… Disabled people are constantly creating an improbable crip future in the face of all that wants to eliminate us… We are the ones who know, more than anyone, the technology of how to really care.”

So, that’s the answer to why we should imagine a future with disability conserved. We, collectively, need all of that knowledge and creativity and expertise. The answer to why we should imagine a disabled future is even more simple. We should do it because that’s what we’re going to get. Contrary to the aims of eugenics, the future will have far more disabled people in it, not fewer. Droughts, floods, resource wars, pandemics and increased pressure on healthcare and housing all point us towards increases in people with chronic illnesses, injuries, and other debilitating conditions. Ironically in fact, this extra-disabled future is brought to you by the same people who brought you eugenics. Thanks to a couple of centuries of mass industrialization, militarization and capitalization, cooked up in the fever dreams of white colonial powers, we are facing a global environmental breakdown of almost unimaginable proportions. And a lot of us are still turning our minds away from that future. That future will be full of disability, and we need the leadership and creative direction of people who know how to get through it.

This is how radically imagining distant futures can help us take actions in the present when our imaginations freeze in the headlights. Pessisism, cycnicism and nihilism are luxuries for people who have never had to imagine their way out of seemingly insurmountable crisis. In her final speech, the legendary science fiction writer Ursula le Guin said, “We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable: but then so did the divine right of kings”.

Walidah Imarisha writes, “For those of us from communities with historic collective trauma, we must understand that each of us is already science fiction walking around on two legs. Our ancestors dreamed us up and then bent reality to create us”.

People living under violent and oppressive systems have always been able to imagine themselves free. If you struggle to believe that that we can get to a better disabled future, remember that disabled people are already equipped to get us there. Piepzna-Samarasinha says, “What would a world radically shaped by disabled knowledge, culture, love, and connection be like? Have we ever imagined this, not just as a cautionary tale or a scary story, but as a dream?”. Consider, what forms of community, what means of survival, what tricks and tools we could use and enjoy if we asked the experts to lead.

And then think about how we get there. Because white disability studies, individual rights, and a charity model of access cannot get us to that future. We need to make a culture-shifting leap in accessibility, through the knowledge and leadership of disabled people, in order to build the communities and systems we will need in the coming emergencies.

Stacey Park Milbern said, “…access.. is only the first step in movement building. People talk about access as the outcome, not the process… yet there is so much more still waiting for us collectively once we build the skillset of negotiating access needs with each other.”

So, most of you are involved in some kind of organizing at some level, and all of you are involved in communities, in families, in schools and networks.

Here’s my closing proposition.

I want you to imagine your group, your project, your committee, your organization, your university, if you committed to full accessibility as a non-optional imperative. What if you said: if our events, our meetings, our classes, our protests are not accessible, then they do not happen at all. What would you need to change?

Whose expertise would you need? What connections and networks would you have to find or create?

Can you you make that commitment?

Choose a not very distant future. Imagine a month. Imagine a year. This work is urgent and it won’t be easy.

So, that’s my closing proposition. Imagine that world. And figure out how we get there.

Thanks.

One thought on “Futures, Imagined: Disability, Eugenics, & Science Fiction”